Reading Renee Gladman

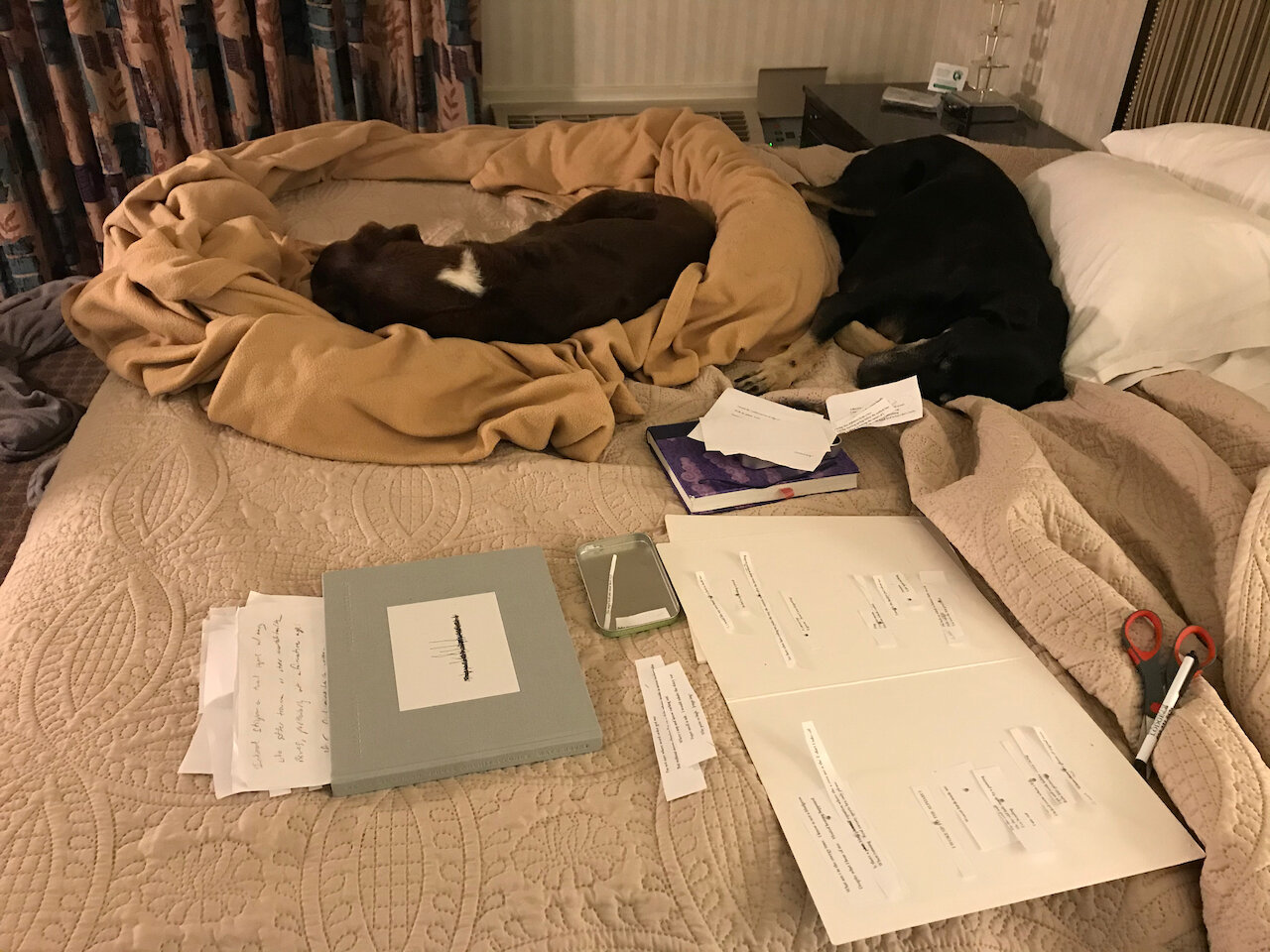

Selecting an armful of books to take when there's a fire: I've done this once before in recent years, so I know which few are most precious to me. I also reach for what, right now, I want to read. This week, I am fortunate and safe, and I want to read Renee Gladman, even if I sometimes struggle to read in the general atmosphere of danger and uncertainty.

I first encountered Renee Gladman’s writing shortly after I became a member of Kelsey Street Press. I set out to read their (then) forty-year catalog of poetry and prose titles, two of which are by Gladman. Published in 2000, Juice is composed of four short stories. I think this is one of her earliest books. Her recent experiments with syntax are more complex and entangling, whereas Juice unfolds in more concise sentences. Years ago, this book made a strong impression on my first reading, primarily because of Gladman's direct but uncanny voice. I also loved that, despite the speaker's forthright manner, each story involves a pivotal, undisclosed event.

The first story, “Translation,” begins: “About the body I know very little, though I am steadily trying to improve myself, in the way animals improve themselves by licking. I have always wanted to be sharp and clean” (Juice, 8).

Then, further: “We have statues that the sky illuminates to such a degree that we live in them. They aren’t mirrors; they are magnificent distractions of great height and fortitude. They are brick and handsome” (Juice, 8)

Places of residence recur in Juice, and Gladman's ongoing exploration of narrative is apparent: time is organized but slippery. The sequence of events is see-through in moments.

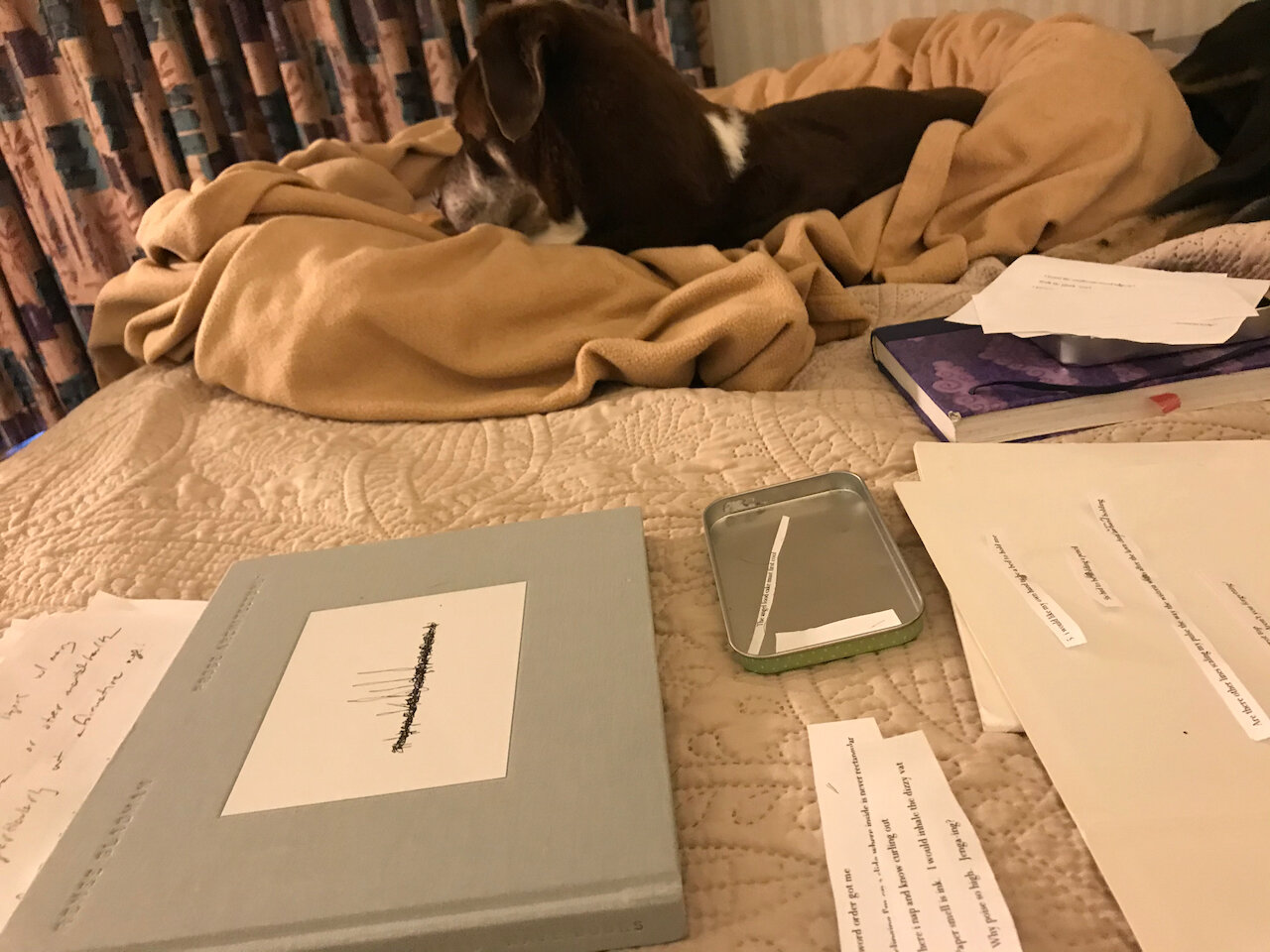

Prose Architectures is the other book by Gladman that I brought with me this week. Published in 2017 by Wave Books, it contains drawings by Gladman that she references in Calamities, a phenomenal prose book published by Wave a year earlier. (If you are unfamiliar with the drawings, you can view some on Wave’s page for the Prose Architectures.) Gladman follows her art's trajectory in these two volumes, shifting her relationship to her medium and pursuing new creative practices. Drawing is not tangential to her writing, but rather a counterpart to her work with sentences. In her introduction to Prose Architectures, Gladman explains:

It seems the shapes I most wanted to represent or most could represent were buildings. I don’t remember setting out with any particular goal in drawing but I do recall clearly feeling that, through drawing, I had discovered a new manner for thinking. Drawing extended my being through time; it made things slow. It quieted language. It produced a sense that thinking could and did happen outside of language. (Prose Architectures, VII)

Gladman is interested in cities. I don't currently live in a city. I live in the Santa Cruz Mountains, but I am interested in containers, and buildings are kinds of containers (as are bodies). For me, Gladman's drawings are charged objects. In reading them, I trace their energy. I have found that staring at these drawings begins in the quiet but then produces language. I write lines in response. Perhaps the drawings hush pressing outside language. Settling into these silent pages, I hear more acutely. Most poems I write are revised and edited over months or years, and I don't know if these lines will turn into poems or resist renovation. Regardless, they feel animated to me, and, right now, I value their vivacity.

Prose Architectures offers buildings in which the mechanical gesture of writing is a factory: this is where letters could be made—or not. The decision to utter words has not yet been reached. Here, I encounter an extended moment without sense, where expression is latent energy. There’s an almost intoxicating excitement to be at rest in that energy.

My lines in response to Prose Architectures:

I've long thought of scaffolding in the context of my poetic practice: I've noticed that some aspects of a draft (lines, stanzas, even ideas) are needed for construction, but I must remove them later to finish the poem. In developing drafts, I sometimes honor the contribution of scaffolding by omitting text but preserving white space where I’ve done so. Those elements that I’ve removed weren’t wrong; they were necessary. In Prose Architectures, Gladman has found a way to centralize a kind of scaffolding. She has crystallized the early moment of expression where its nascent gesture and supports are one, mechanically: an instrument in the hand.

In Gladman’s words:

I realized that if I were to write without making sense I would be doing exactly what I’d begun to do: I would draw! I would say to people in reference to the drawings: “This is language with its skin pulled back.” (Prose Architectures, XI)

My lines in response to these drawings obviously wear the skin of language. Still, they are prompted by being pulled back: their sequence reversed or rendered sheer. I'm grateful to begin again in this original silence.